Colorado and the IWW

Part I:

By Douglas P. Marsh, May 2022

“The strike was called November 9th, 1903. ... The whole state of Colorado was in revolt.” - Mother Jones

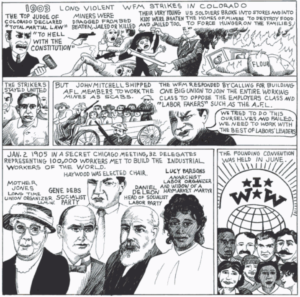

It’s well known how in 1905 the famous Big Bill Haywood helped found the Industrial Workers of the World in Chicago with Mother Jones, Lucy Parsons, Eugene V. Debs, and others. Fewer know that Colorado – specifically the Colorado Labor Wars – was where Haywood and several other wobbly founders forged bonds of solidarity among miners and learned the pitfalls of business unionism. Or that it’s where Haywood ran for governor, albeit from an Idaho jail cell.

And very few know that Colorado’s most successful strike took place under IWW leadership, during an overlooked surge in the union’s influence in 1927-1928.

Western Federation of Miners and the founding of the IWW

Approaching the turn of the 20th century in the American west’s mining industry, big capitalists were putting the squeeze on labor and conditions were increasingly mean. Workers from Idaho, Montana, and Colorado began organizing and in 1893 would form the Western Federation of Miners in Idaho.

WFM’s initial strikes took place in Colorado, with Cripple Creek’s first miner’s strike of 1894, and after that in Leadville in 1896-1897. Haywood joined the WFM in 1896 as did another of IWW’s earliest members, Adolphus S. Embree, in 1899.

In Idaho, 1899, mine workers, armed and masked, hijacked a train and blew up mining equipment belonging to operators that refused to sign a WFM contract. The equipment was targeted because it was the cutting edge in mining technology and thus extremely expensive.

The event terrified bosses on both sides of the national border. At the time Haywood was also in Idaho, while Embree was farther north in British Columbia, both mining precious metals. Idaho Governor Frank Steunenberg declared martial law, convincing President McKinley to deploy soldiers and detaining over 1,000 men in a barn without trial.

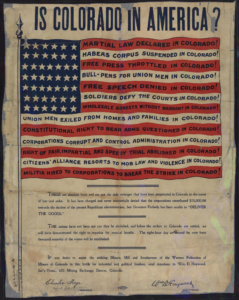

By 1903 tensions would erupt into the Colorado Labor War, where employers brought against workers the most systematic use of violence in U.S. labor history. In the face of brutal suppression, miners executed multiple coordinated, direct actions in at least six mining towns throughout the state in 1903 and 1904.

Galvanized in these and other struggles in the region, radical factions within the WFM sent delegates to Chicago in June of 1905 to help found a new organization to compete with the American Federation of Labor in uniting workers from different industries.

The IWW was founded as AFL’s radical alternative – staunchly international and anti-capitalist, and fiercely critical of the AFL’s privileging skilled labor and tolerating nativist sentiments.

Back in Idaho, Steunenberg was assassinated in a bombing outside his Caldwell residence in late December, 1905.

Colorado and IWW’s early years

The IWW’s second convention in 1906 began in open conflict and concluded in schism.

As with many revolutionary organizations, the IWW was internally divided from the outset. Many members drawn from the AFL brought the federation’s reformist tendencies, while WFM dual-carders (workers affiliated with two unions) included members with more conservative beliefs.

“The struggle for control of the organization formed the Second convention into two camps. The majority vote of the convention was in the revolutionary camp. ... On the adjournment of the convention the old officials seized the general headquarters, and with the aid of detectives and police held the same, compelling the revolutionists to open up new offices.” - Vincent St. John

A few months after the convention, Big Bill Haywood was arrested in Denver at WMF headquarters and transported to Idaho, where he was accused of orchestrating the assassination of former governor Steunenberg. From a Boise jail cell, he won over 16,000 votes for governor of Colorado on the Socialist Party of Colorado ticket while designing WFM posters and reading Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle. By the end of 1907, the WFM would cut ties with IWW. Haywood left the WFM in 1908.

Dual-carding wobblies were likely involved in continuing labor disputes in Colorado, including the infamous Ludlow Massacre in 1914. The IWW had held free speech rallies in Denver in 1912 and 1913, and A.S. Embree was seen during the long strike (1910-1914) which preceded the massacre and other events of the Colorado Coal War.

In 1916 IWW leadership determined to wage a major campaign, authorizing “an appropriation of $2,000.00 be made for organizing the miners of California, Nevada, Arizona, Colorado, Montana, Utah, Idaho” (Proceedings of the Tenth Convention of the Industrial Workers of the World. Chicago, 1916, page 61). Embree and another wobbly, Frank Little, were two of the external organizers sent into the field. They arrived to find the IWW forgotten to most miners and a united front among bosses and government agencies.

The Mountain West and the Fall of the IWW

“Guns, revolvers, machine guns came to Bisbee as they did to the front in France. Shoot them back into the mines, said the bosses.

“Then on July 12th, 1,086 strikers and their sympathizers were herded at the point of guns into cattle cars in which cattle had recently been and which had not yet been cleaned out; they were herded into these box cars, especially made ready, and taken into the desert. Here they were left ... without food or water to die.”- Mother Jones

The U.S. entered World War I in the spring of 1917. By early summer, workers with IWW Local 800, fighting for better conditions in Arizona’s copper mines, were ready for action. A.S. Embree had been organizing miners operating out of Bisbee, with another IWW leader coordinating from Phoenix. Just before the strike, the Phoenix offices were moved to Salt Lake City, and Embree was cut off.

Though over 2,000 workers joined the Bisbee strike, a posse of even more assembled on behalf of the bosses and selected 1,200 deportees to load onto a train, later to be dumped in the desert over a hundred miles away. They were held in Columbus, New Mexico for over two months by federal troops who had been on the hunt for Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa.

It was the largest deportation in U.S. labor history.

After release, A.S. Embree would travel north to copper mine strikes in Butte, Montana where IWW organizer Frank Little was lynched on August 1, 1917. Little was the second of three early IWW martyrs along with Joe Hill, an IWW songwriter, organizer, and activist executed by firing squad in Utah in 1915, and Wesley Everest, a former serviceman and lumberjack who was lynched by a mob while defending his union hall following the 1919 Seattle General Strike.

Embree earned a reputation in subsequent strikes in and around Montana as IWW’s “ableist tactician” while also returning to Tucson, Arizona to face down incitement of riot charges over events at Bisbee. He was targeted by federal agents from 1917-1920 who provided evidence to prosecutors in Idaho, where he was sent to state prison from 1921 to 1924 for “criminal syndicalism.”

Disrupting the copper industry during war-time production led in part to the federal government’s overwhelming and devastating attacks on the IWW. These began on September 5, 1917, when state and local forces initiated raids against IWW offices, as well as private residences of the union’s leaders, all across the U.S.

In the end over 150 wobblies were arrested and charged under a new Espionage Act. IWW co-founder Eugene V. Debs would be arrested in June of 1918 and sent to prison in April 1919 for speaking publicly against the war. Big Bill Haywood fled to Russia in 1921, where he died seven years later aged 59.

References

Campbell-Hale, Leigh. Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike. Diss. University of Colorado at Boulder, 2013.

Jones, Mary Harris. Autobiography of Mother Jones. Charles Kerr, 1925. <https://archive.iww.org/history/library/MotherJones/autobiography/>

Linder, Douglas. "The Trial of William 'Big Bill' Haywood." (2007). <https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1023972>

Mellinger, Philip. "How the IWW Lost Its Western Heartland: Western Labor History Revisited." The Western Historical Quarterly 27(3) (1996): 303-324.

St. John, Vincent. The IWW – its History, Structure and Methods. Edited by Mark Damron, 2001; Originally published by IWW PUBLISHING BUREAU in CHICAGO, 1917.

Taft, Philip and Ross, Philip. "American Labor Violence: Its Causes, Character, and Outcome," The History of Violence in America: A Report to the National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence, ed. Hugh Davis Graham and Ted Robert Gurr, 1969.

Part II

A.S. Embree returns to Colorado

Entering the mid 1920s, the IWW was preoccupied both with the legal defense of its many imprisoned members as well as internal debate over whether said defense was part of the mission proper of the organization. Meanwhile, coal industry wages began to stagnate and fall.

After working and organizing for over 25 years in the mining industries of the American mountain west, and subsequent targeting by state and federal agencies, IWW organizer A.S. Embree was sent to an Idaho prison in 1921 for “criminal syndicalism.” He emerged in 1924 onto probation, blacklisted and destitute.

The IWW was divided – in the leadership between communists, accused of conspiratorially steering the organization according to the party program of the Third International, and anarchists who favored decentralization; and in the membership on the same issue, loyalties further divided on the question of Big Bill defecting to Bolshevik-led Russia while his counterparts went to Leavenworth.

Embree moved his family to Chicago to be closer to IWW headquarters. He was sent to the Colorado coal fields in March 1926, where wobblies had been laying the groundwork. A 1932 historical account puts IWW organizers in the area as early as December, 1925. Another from 1963 claims IWW field organizer Frank Jurich formed Industrial Union 210-220 in September. But the July, 1924 edition of Industrial Pioneer contains the following brief report on page 43:

"The Metal and Coal Miners’ Industrial Unions Nos. 210-220 held a convention at Butte, Mont. Steps were taken to expand the organizations. The Metal miners are supporting the miners’ strike at Santa Eulalia, Mexico. John Martin is now Secretary-Treasurer of 210-220."

-

“The IWW at Home and Abroad.” Industrial Pioneer, Vol 2(3). July, 1924.

United Mine Workers of America were also organizing miners in Colorado, who numbered between 12 and 14 thousand and were increasingly agitated by working conditions and stagnant and falling wages. Dual-carding (joining both unions) or organizing exclusively with the IWW became more prevalent. “Their betrayal by international officials of the U.M.W.A. in 1921-1922 has disgusted them with that organization and they are now willing to listen to what the I.W.W. has to offer,” said Embree in one of his first reports.

After three months of organizing and reports back to headquarters, Embree requested to reunite with his family in Chicago. He did, but before long he was sent back to Colorado, seen as too big a threat by holders and seekers of union officer positions. By March of 1927, Embree would report IWW membership numbers from the Colorado coal fields increased by a factor of five. Along with IWW leader and organizer Kristin Svanum, Embree would head up the most successful workers’ strike in the history of the state of Colorado.

The rise of IWW Industrial Union 210-220

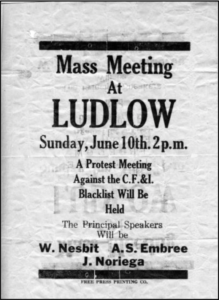

A.S. Embree and Kristin Svanum did the slow, quiet work of organizing throughout the year of 1926 in southern Colorado, basing operations out of Walsenburg, 30 miles north of Trinidad and 20 miles north of the site of the Ludlow Mine Massacre of 1914. By December they opted to go public, inviting the famous labor activist Elizabeth Gurley Flynn to speak in Pueblo, Aguilar, and Walsenberg.

In March 1927, IWW Industrial Union 210-220 held a publicized meeting where they passed resolutions in support of political prisoners, just as the president of the United Mine Workers of America local District 15 issued a public statement denying any intention of strike actions in the Colorado region. UMWA’s most important bargaining unit did in fact strike at the end of March, eventually to be defeated and dissolved. Colorado miners feeling betrayed by UMWA leadership continued to turn increasingly to IWW IU 210-220.

More mass meetings were held as spring turned into summer, rallying around firings and blacklisting of union workers. Embree sent some blacklisted workers with money to New Mexico and northern Colorado to work as IWW organizers. IU 210-220’s ranks swelled to close to 1,000 members. In early July they held the Walsenburg District Conference, attended by representatives from 36 mining camps.

On July 24, 1927 IU 210-220 called for “a convention of all western coal miners, regardless of union affiliation, said convention being given power to call a strike of all western coal miners,” according to an article from July 27 in Industrial Solidarity. On August 6, 1927 when the international executive board for the IWW called for a three day work stoppage to protest the approaching execution of the political prisoners Vanzetti and Sacco, the workers of IU 210-220, centered in the Walsenburg district, were the only ones to take action. They staged walkouts for two days. The walkouts started on August 8 and according to the sheriff of Huerfano County over a thousand miners participated.

Embree, Svanum and other organizers were visited the next day by the State Industrial Commission (formed in response to public outcry after the Ludlow Mine Massacre in 1914), who told them that the walkout was illegal because the union had not given 30 days’ notice. At emergency meetings, Embree asked workers to vote, encouraging them to postpone further strike actions. The workers voted almost unanimously to end the strike. Svanum chaired as the group met again in Pueblo in September, issuing new, revised demands focused around wages, hours, working conditions and procedures and setting a strike date for October.

The Colorado Coal Strike of 1927 begins

"Our plans at the present is to answer by giving blow for blow, by strikes. When any member is discharged for union activity, we shall answer by a STRIKE IN ALL THE MINES OF THE COMPANY INVOLVED."

- Kristin Svanum, fall 1927

The strike notice sent by IWW IU 210-220 was rejected by the State Industrial Commission on grounds that IWW did not represent the miners, an attack regularly used against workers organizing under the union throughout its history. The General Strike Committee pushed the date back ten days in response, to October 18, 1927, feigning a stall for time to hold strike votes. They were spreading north into more mining operations, as well as agriculture.

From Oct. 10-15 wobblies were beaten, robbed, arrested and run out of towns by mayors, city councils and lynch mobs throughout the southern Colorado mining district. On Oct. 11, a newspaper reported IWW flyers circulating in northern beet fields, with messages in Spanish encouraging Mexican workers to organize and take back their land. On Oct. 13, a United Mine Workers of America official predicted publicly that the strike would be called off.

On Oct. 17, IU 210-220 held four meetings, one in Lafayette with between 1,500 and 4,000 attendees. The southern area miners met in Aguilar, while a mob 75-strong ransacked and burned the IWW union hall in Walsenburg.

CF&I Archives photo right: 1. Nick Mavroganis; 2. Frank Mendas; 3. A. S. Embree; 4. Alberto Martinez; 5. Tom Garcia; 6. Nenesio Adillo; 7. John Maes; 8. unnamed; 9. Paul A. Sidler; 10. John Mariega; 11. A. K. Payne; 12. Gumersindo Ruiz; 13. Walter Chatterbock; and 14. Jose Villa at the Walsenburg IWW hall.

The strike began with unprecedented participation on Oct. 18, 1927, as half the miners in the state struck and pickets spread wherever mines stayed open. Over the next two days, statements against use of violence were issued by the General Strike Committee and the IWW.

Within a month the same workers would experience the state employing both violence and ad hoc legal maneuvers in opposition to their peaceful and straightforward demands for justice.

References

Campbell-Hale, Leigh. Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike. Diss. University of Colorado at Boulder, 2013.

Dubofsky, Melvyn. We Shall Be All: A History of the Industrial Workers of the World. Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1969.

McClurg, Donald J. "The Colorado coal strike of 1927—tactical leadership of the IWW." Labor History 4(1) (1963): 68-92.

Svanum, Kristin. “Discrimination to be met with repeated strikes in colorado area.” Industrial Worker, Vol. IX, No. 41, Whole No. 565. Oct. 15, 1927.

Part III

The Colorado Coal Strike of 1927

‘To hell with martial law’ – Kristin Svanum

When strikes began to break out in Colorado coal mines in the spring of 1927, it was far from spontaneous. Industry wages had been stagnant for years. Conditions for workers had declined steadily. The business unions had betrayed their rank and file members. The Industrial Workers of the World had regained a major foothold in the region.

The IWW had redevoted resources to organizing the mining industries of the American mountain west toward the end of 1924. The number 200 is the union's designation for the mining and energy industry, with 210 for miners and 220 for energy workers. Industrial Union 210-220 formed during the latter half of 1924 and in 1926, experienced organizers Kristin Svanum and A.S. Embree began to help workers coordinate their struggle and to support the IU as it continued to build grass-roots power.

Mass meetings and actions throughout the spring of 1927 led to confrontations with Colorado's State Industrial Commission and a tense game of cat and mouse through that summer between authorities and strike leaders. IWW union members were in the meanwhile frequently jailed for organizing activities and subject to violence by hired goons.

By October 21, 1927 the Colorado Coal Strike strike was on the front page of both major Denver daily newspapers, where it would stay until the conflict concluded. They soon picked up on a 19-year-old miner’s daughter and native of the mining town of Walsenburg. The young woman was hospitalized after being trampled by a sheriff’s horse at a picket just south of Ludlow early in the strike. “Flaming Milka” Sablich, the girl in red, began to emerge as a protest icon.

Picketing had been declared illegal in Colorado by state law in 1920. Organizers took lessons from IWW free speech fights in the 1910s and exercised rights to use public roadways and assemble on public properties.

IWW leader Kristin Svanum was arrested picketing in Trinidad on Oct. 23. In the north, low response to the strike call prompted organizers to assemble a convoy of 134 vehicles with over 500 strikers to spread the message.

The group set into motion on Oct. 26, just as the governor of Colorado issued a public statement to the press denouncing the IWW, and spent several days campaigning through the north fields.

The governor met the chairman of the General Strike Committee the next day while fuel companies and the Industrial Commission began offering the first pay increases. Raises were deemed inadequate by the strike committee. Leaders from the Colorado National Guard met with Industrial Commissioners and company bosses on Oct. 30 and afterward warned strike leaders to cease all activities and gatherings.

But the mass meetings were constant, with music and local and national speakers regularly addressing crowds. Svanum was out of jail, and participated in a vote to resume picketing in a mass meeting in Walsenburg. As the parades and gatherings grew in size and frequency, Colorado Fuel & Iron was scrambling, publicly reporting increased production while quietly laying off half its Pueblo steel production staff, 2,500 workers, due to lack of coal for operations on Nov. 3.

The next day, the governor reassembled the same state police force that he had once abolished in fulfillment of campaign promises. He chose Louis Scherf for his chief. Scherf was second in command for strike-breaking actions in 1922 under the same commander who led anti-worker forces during the Ludlow Massacre in 1914. At Ludlow, 25 people were killed. Eleven were children – burned alive.

The Columbine Mine Massacre

The new state police made their first move on November 5, 1927 at Berwind Canyon, where Milka Sablich had been trampled not long before. Chief Scherf led 17 men into confrontation with around 500 miners, arresting seven and fighting the crowd with clubs and fists.

The governor authorized giving Scherf five times more men and military-grade equipment on that same day. Strike leadership, including Kristin Svanum and A.S. Embree, were arrested in midnight raids on Nov. 6 in Walsenburg and transported in secret to Pueblo, where they were put under heavy guard.

Strikers in the north responded by blockading roads and shutting down the Columbine mine. On Nov. 8, a group of 800 clashed with police there. The strike continued to gain strength despite the identifiable leadership being jailed. The deep organizing done by Embree and Svanum over a year and a half and the radical democratic procedures used in the strike committees had equipped the miners to carry on no matter who was arrested.

Scherf’s forces numbered close to 60 when they raided the Nov. 9 IWW meeting in Walsenburg, arresting all speakers and again fighting with the crowd. The day after that, a combat aircraft and three other planes scattered a gathering of 3,000 people at the Ludlow Monument.

Mass meetings continued to spread unabated. A rally in Denver on Nov. 13 in support of the strike drew over 2,000 people. The next day to the north at the Columbine mine, sheriffs attempted to arrest protest leaders only to have them freed by the crowd. Mine officials threatened to shoot trespassers, who claimed the right to cross the company’s property in order to access a post office and a school.

The Columbine mine resumed operations on Nov. 16 with extra police forces transferred in by the governor, machine guns strategically mounted, and electrified, barbwire fencing. Striking miners persisted in parading and assembling nonetheless.

On Sunday, Nov. 20 a rally was held in Boulder that drew over a thousand people. The group was rumored to be planning a march on the Columbine mine property and the police brought in emergency reinforcements in the middle of the night.

500 miners were confronted at the Columbine gate early the next morning by Scherf himself, leading a force of 20 armored police. Asked who their leaders were, they replied, “We all are.”

The crowd burst through the gate after Adam Bell, an IWW national leader, climbed the fence and was pulled over and beaten unconscious by police. Not long after the miners got through the gate police opened fire into the crowd at close range, killing six and wounding 20.

The end of the Colorado Coal Strike of 1927

The General Strike Committee for IWW’s Industrial Union 210-220 responded to the mass casualties inflicted by state police forces at the Columbine Massacre on November 21, 1927 by ordering union workers to stay home. The National Guard was on high alert and the strike committee decided to deescalate.

Mining operations resumed, using scab labor under National Guard supervision. Perfunctory hearings by the coroner’s office concluded no wrongdoing by police. The newspapers spent a few days eulogizing the dead, then commenced dutifully printing the versions of events provided by police and company officials.

Public pressure brought about the Colorado Industrial Commission’s Dec. 12 announcement of formal hearings, which were held from Dec. 19 to Feb. 15 in Cañon City, Walsenburg, Trinidad, and Colorado Springs.

Thousands of miners were still out on strike, but were subjected to mass arrests any time they gathered in numbers. When the hearings came to Walsenburg on Jan. 12, over 500 wobblies gathered for a parade starting from their IU 210-220 hall a few blocks from the courthouse.

The mayor of Walsenburg, who had led a mob to destroy the IWW hall three months earlier, ordered the state police chief, Scherf, to intercept. Police charged the marchers, then gave chase and opened fire on the crowd and the union hall. They killed a wobbly in the hall, Clemente Chavez, and a 16-year-old bystander, Celestino Martinez.

This time the hearings by the coroner’s office were passed off to the district attorney and a jury concluded the police were in the wrong and had shown a total disregard for human life. Nevertheless, no police were charged or punished.

When the Industrial Commission hearings finished on Feb. 18, 1928, IWW organizer A.S. Embree called for a vote to end the strike. Colorado miners returned to work having won the only wage increases in the U.S. coal mining industry between 1928 and 1930.

IWW in Colorado: Then to now

The tactics used by miners during the Colorado Coal Strike of 1927 were some of the most diverse and effective ever seen in the modern labor movement. Radically democratic procedures and genuine commitments to peace (when possible) set IWW IU 210-220 apart from more or less all its labor peers up to that time.

After the strike ended, the Rocky Mountain Fuel Company courted the United Mine Workers of America to undermine IWW influence in the Colorado coal fields. IWW national leadership worked to sabotage A.S. Embree’s rising star.

By 1932, when one of the first comprehensive histories of the IWW was written, the organization’s membership in Colorado had decreased to 500 or less. A.S. Embree left the IWW to focus on organizing and labor reporting with Denver-based Mine Mill in 1937. By the mid 1950s and the height of the U.S.’s second red scare, the national organization was down to a few hundred members or less in perhaps its ultimate nadir.

The wobbly spirit did not (as it will never) die forever. Lifelong IWW member and writer Arthur J. Miller wrote of his own stint in the mountain west mining industry in the 1970s shortly after a tragedy. Miller recounted drifting into northern Idaho not long after 91 men perished in the nearby Sunshine Mine, and provided a snapshot of the working conditions.

Miller’s experience and perspectives are consistent with the attitude which came to reestablish the IWW with a local chapter in Denver that dates back to the late 90s or early 2000s. An IWW working group is also building capacity in southern Colorado, centering operations in Colorado Springs.

If you are interested in organizing at work and keeping alive the spirit of A.S. Embree, Kristin Svanum and other working class heroes, contact your local IWW branch today. In the state of Colorado, fellow workers can be reached at denveriww.org

References

“A history of the Colorado Coal Field War.” Colorado Coal Field War Project. N.D. Available at: <https://www.du.edu/ludlow/cfhist3.html>

Campbell-Hale, Leigh. Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike. Diss. University of Colorado at Boulder, 2013.

Miller, Arthur J. “The Legacy of the Bunker Hill Mine.” Available at: <https://archive.iww.org/culture/articles/wpl/bunker1/>

(All) References

“A history of the Colorado Coal Field War.” Colorado Coal Field War Project. N.D. Available at: <https://www.du.edu/ludlow/cfhist3.html>

Campbell-Hale, Leigh. Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike. Diss. University of Colorado at Boulder, 2013.

Dubofsky, Melvyn. We Shall Be All: A History of the Industrial Workers of the World. Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1969.

Gambs, John S. "The Decline of the IWW." The Decline of the IWW. Columbia University Press, 1932. Available at: <https://libcom.org/article/decline-i-w-w>

IWW. Proceedings of the Tenth Convention of the Industrial Workers of the World. Chicago, 1916. Page 61. <https://archive.org/details/16Proceedings10thConvIWW>

Jones, Mary Harris. Autobiography of Mother Jones. Charles Kerr, 1925. <https://archive.iww.org/history/library/MotherJones/autobiography/>

Linder, Douglas. "The Trial of William 'Big Bill' Haywood." (2007). <https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1023972>

McClurg, Donald J. "The Colorado coal strike of 1927—tactical leadership of the IWW." Labor History 4(1) (1963): 68-92.

Mellinger, Philip. "How the IWW Lost Its Western Heartland: Western Labor History Revisited." The Western Historical Quarterly 27(3) (1996): 303-324.

Philip Taft and Philip Ross, "American Labor Violence: Its Causes, Character, and Outcome," The History of Violence in America: A Report to the National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence, ed. Hugh Davis Graham and Ted Robert Gurr, 1969.

St. John, Vincent. The IWW – its History, Structure and Methods. Edited by Mark Damron, 2001; Originally published by IWW PUBLISHING BUREAU in CHICAGO, 1917. <https://archive.iww.org/about/official/StJohn/>

Svanum, Kristin. “Discrimination to be met with repeated strikes in colorado area.” Industrial Worker, Vol. IX, No. 41, Whole No. 565. Oct. 15, 1927. Available at <https://industrialworker.org/colorado-coal-strike-part-1/>

“The IWW at Home and Abroad.” Industrial Pioneer, Vol 2(3). July, 1924. Available at: <https://libcom.org/article/industrial-pioneer-july-1924>

Image credits

Cover page – Written from jail per Melvyn Dubofsky’s We Shall Be All: A History of the Industrial Workers of the World. Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1969. Graphic design by author.

Page 3 – from Alewitz, Mike, Coe, Sue, and Jones, Sabrina. Wobblies!: A graphic history of the Industrial Workers of the World. Verso, 2005.

Page 4 – “Is Colorado in America?” Public domain image: <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Is_Colorado_in_America.jpg>

Page 5 - “Photograph of a group of workers deported during the Bisbee Deportation, a strike by the Industrial Workers of the World, taken in Columbus (N.M.).” Arizona State Library, Archives and Public Records. History and Archives Division. <https://azmemory.azlibrary.gov/digital/collection/histphotos/id/15163/rec/1>

Page 6 - “Joe Hill Ashes.” Retrieved from: <https://archive.iww.org/sites/default/files/images/joehill_ashes.preview.jpg>

Page 6 - “Frank Little grave site.” Retrieved from: <https://explorepartsunknown.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/100516_rt_d8231-e1488905574340.jpg>

Page 8 - “Mass Meeting at Ludlow.” INR 1300-7, CF&I archives. Found in Campbell-Hale, Leigh. Remembering Ludlow but Forgetting the Columbine: The 1927-1928 Colorado Coal Strike. Diss. University of Colorado at Boulder, 2013.

Page 9 - “Colorado Fuel & Iron spy photo of A.S. Embree et al.” Available at: <https://www.historycolorado.org/story/2021/04/19/x-xx-and-x-3-spy-reports-colorado-fuel-iron-company-archives>

Page 10 - “Girl Leader of the I.W.W. Strikers.” Retrieved from: <http://www.kevincmurphy.com/uatw-legacies-labor.html>

Page 12 - “Troops Take Charge at Columbine Camp.” Retrieved from: <https://files.libcom.org/files/styles/wide/public/columbine.jpg>

Page 12 - “Police Turn Guns on Colorado Miners.” Retrieved from: <https://historicly.substack.com/p/the-other-massacre-in-columbine>

Page 12 - “Lest We Forget.” Retrieved from: <https://industrialworker.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2020/12/131989701_1404178289-2048x1365.jpg; https://industrialworker.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2020/12/columbineshoot.jpg>

Page 13 - “Exterior of the Walsenburg IWW Hall.” Retrieved from: <https://reuther.wayne.edu/node/11365>